In a world fuelled to promote efficient, convenient, and time-saving processes we can’t help but clutch on and bring to question the moments when tradition overrules and triumphs change. These moments exist, they are played out day in and day out, they are subconscious, unseen, and require no recognition. But we can’t help but ask, what is the deciding factor that encourages tradition over efficiency? What feeling, sense, outcome do we require to decipher when tradition is more important than convenience?

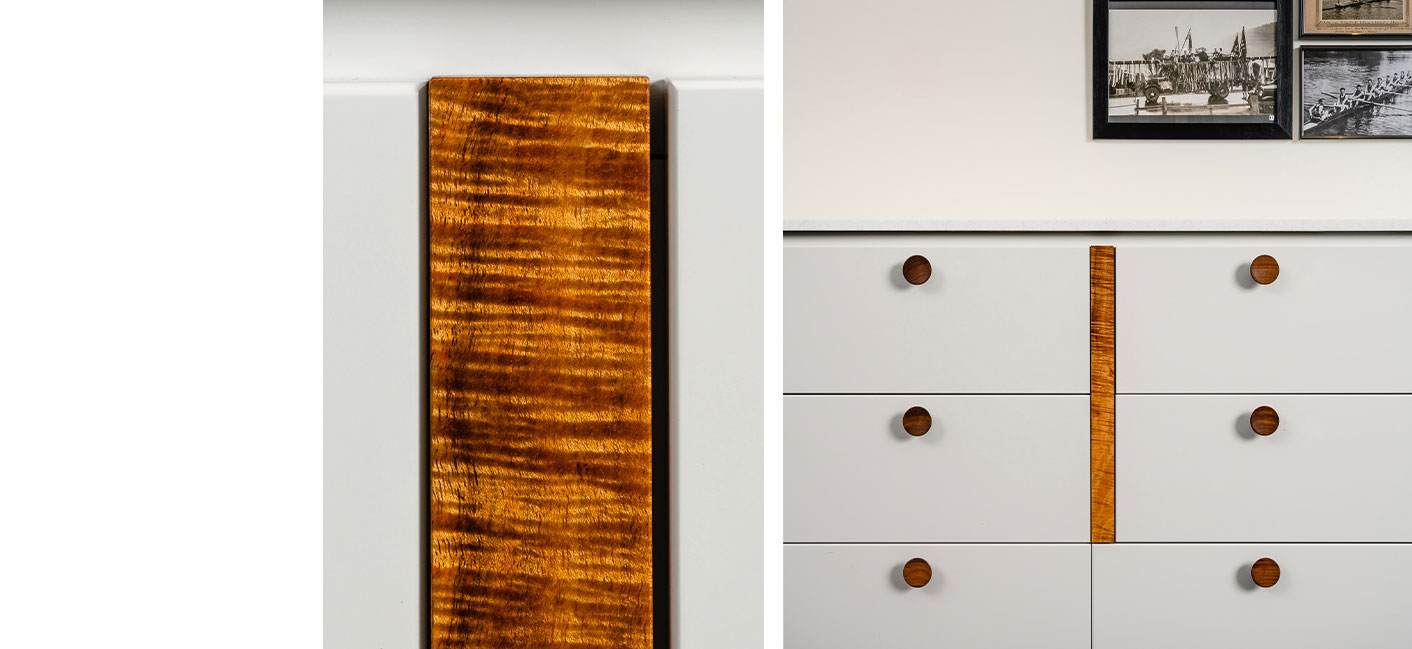

Take the concept of ‘‘knocking-in” the cricket bat. For those that don’t know, “knocking-in” is the process of preparing a new cricket bat so that it’s ready for use. Some use a mallet for this and apply linseed oil to prevent cracks, and others have their own unique way of preparing it, but the vital outcome is that the timber fibers are compacted together to create a smooth and durable surface. As parents or for anyone who doesn’t play cricket it’s extremely annoying, it’s six hours of loud repetitive noise, and it brings up the question of why? Why would we purchase an item that is not ready for use? Why would a cricket bat, during its manufacturing process not be fit for purpose or completely resolved? It seems strange that in the world we live in we haven’t yet resolved these requirements. Does this instead indicate that we actually need these traditional processes as a way to prepare us or to find value? And if we are to think like this, what do these personal processes say about our practice? At what point does tradition become valued and triumph change?

Forbes in their article How innovation can keep traditions alive in modern business discusses this fine balance between integrating tradition and innovation to ensure brands and organisations remain current and competitive in our ever-changing world. They unveil an interesting concept in their discussion that considers how traditions, passed down from generation to generation, ‘are anchors in our lives and form a fundamental part of our identity’ (1). It brings to light a notion of nostalgia, one that values an intricate relationship that exists in our experience of process rather than the experience of the outcome. For the cricket player, the knocking in of a new cricket bat is a fundamental step of ownership, and yet, would this then represent something entirely larger than simply ensuring that the timber is durable and ready for use? Does this process implicitly bind a player to their bat and in turn prepare them for their practice?

Much like the ideas highlighted in the article by Forbes, this anecdote of the knocking-in of a cricket bat indicates that there is an undercurrent of value present when tradition triumphs over convenience and efficiency. What other processes do we apply to our practice that come from tradition, and what do they say about the deliverable. Because, as much as the noise of the cricket bat hitting the mallet frustrates us, it represents something more profound for the player.

A subtle profoundness where the smell of freshly cut timbers, the feel, the texture, and the new form are material representations of the place where physical readiness coexists with the mental rehearsal that is often inherent in expressions (sporting and otherwise) that are grounded in tradition. It brings to light that other traditions, although trivial in their manner, should not be let go in fear of losing their fundamental value but instead harnessed and embraced. Often.

- Soulaima Gourani, How Innovation Can Keep Traditions Alive in Modern Business (2019) [online], Forbes, available at: <https://www.forbes.com/sites/soulaimagourani/2019/11/27/how-innovation-can-keep-traditions-alive-in-modern-business/?sh=16bf6a4bbe28>