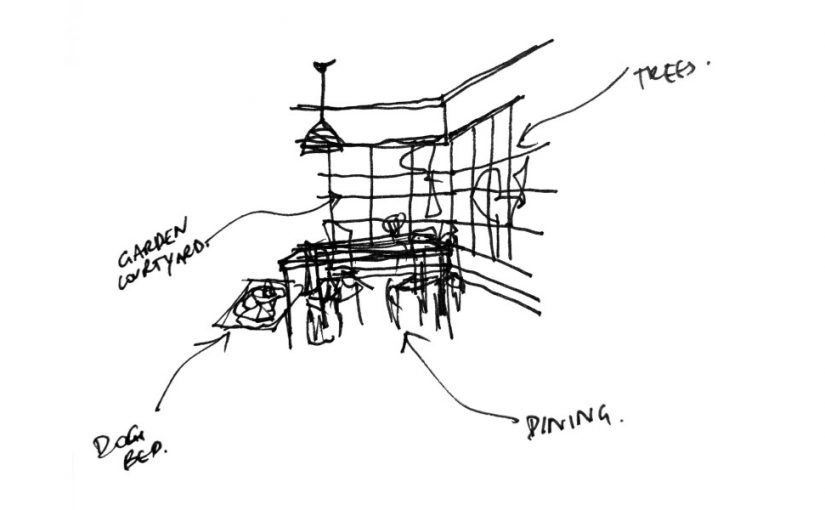

There is something magical about watching a sketch evolve. The raw nub of an idea gradually evolving from simple marks into a physical expression that captures a concept and articulates complex thoughts. Each mark is attended to yet simplified, requiring no further description — an abstract expression of space, interior or exterior as experienced by the viewer.

Expression is no longer confined to a realistic rendered approach but rather one that acknowledges form, complexities in movement, and the inherent qualities of a site. In our design practice, sketching gives invaluable direction and adaptability to our thinking. It doesn’t restrict us from considering how walls could replicate the profile of trees or how ceilings could behave like clouds. It’s open-ended; it has no limitations. Yet does our industry still value sketching as a tool for expression? Has technology, although bearing beneficial and advantageous properties to the industry, triumphed over respect for the simplicity of sketching?

Richard LePlastrier, an Australian architect, captured a profound appreciation of the act of drawing perfectly. His work as an architect is derived from a deep respect for his experience of place, where he can translate this experience through sketch. In an interview by the Sydney Living Museum (1), his discussion of art teacher Lloyd Reece who taught him throughout his architecture degree, inspires and reminds us of the need to draw as designers. Furthermore, it highlights how sketches should be shared, created, expressed not just to ourselves but to those we design for. His discussion draws attention to our modes of working today, where we sometimes shut off our expression to only ourselves. Has new technology reduced the value in raw expression? Maybe we don’t feel our clients value this process?

These new technologies undoubtedly give us the ability to draw 2D and 3D spaces more effectively and dramatically change the scale we can design in. However, does this ability to render a close to realistic visual of a space diminish the value of the storytelling that can exist in the preliminary stages of a design when sketching? For LePlastrier, sketches gave an ability to tell a story, a story where each stroke was a deliberate and direct correspondence to a site or history.

Sketches do not need to be technical or complicated to be appreciated. They should convey a story, perhaps as simple as how a passage through a home is derived from a curve in a tree branch. A story that begins with a pencil touching paper, an observation, an expression, translated through gesture.

- Richard LePlastrier, 2021. Richard LePlastrier – Extended interview (2016) [online] Sydney Living Museums, available at: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rGI-bixNBCE>.

Article written by Valentine Interiors & Design